Litouwen houdt braaf de deur dicht.

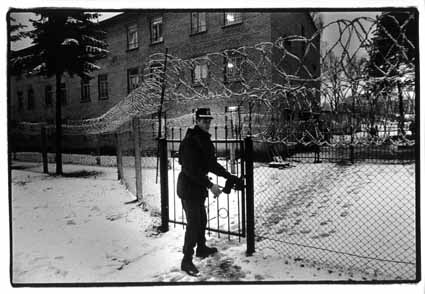

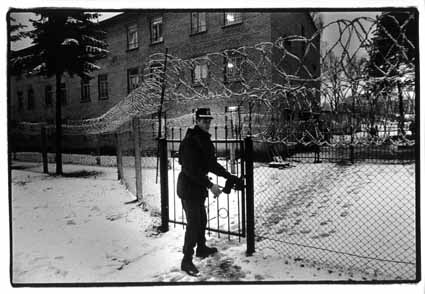

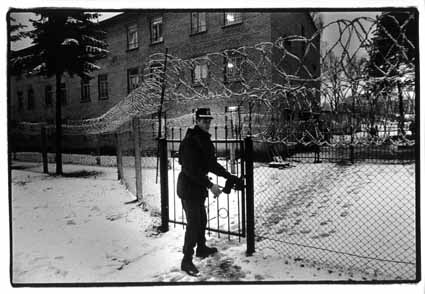

![]() In een oude kazerne van het Rode Leger in Pabradé, Litouwen,

bevindt zich een gevangenis voor gestrande illegalen. Van de tweehonderd vluchtelingen uit landen als India,

Pakistan, Angola, Sri Lanka, Rusland, Azerbejan en Wit Rusland is niemand

van plan om in Litouwen te blijven.

Deze meest zuidelijke Baltische republiek wordt door mensensmokkelaars slechts gebruikt als doorvoerhaven naar

het beloofde land: West Europa.

In een oude kazerne van het Rode Leger in Pabradé, Litouwen,

bevindt zich een gevangenis voor gestrande illegalen. Van de tweehonderd vluchtelingen uit landen als India,

Pakistan, Angola, Sri Lanka, Rusland, Azerbejan en Wit Rusland is niemand

van plan om in Litouwen te blijven.

Deze meest zuidelijke Baltische republiek wordt door mensensmokkelaars slechts gebruikt als doorvoerhaven naar

het beloofde land: West Europa.

Ondanks de relatief lage aantallen is aan alles duidelijk dat de

vluchtelingen in Litouwen niet gewenst zijn. Hoge rollen prikkeldraad omspannen de kazerne en er lopen

agenten met herdershonden rond het complex. Wachttorens houden de omgeving in de gaten.

Fotograaf

Piet den Blanken bezocht de gevangenis en vroeg de vluchtelingen waar ze het liefst naartoe wilden.

Duitsland en Nederland werden het meest genoemd. Daar kreeg je na aankomst meteen een eigen huis en

een baan, wisten de migranten zeker.

De smokkelaars hebben er belang bij om dit soort mythen in

stand te houden om zo de drang naar Europa op te voeren. Maar voor de gevangenen in de Litouwse kazerne

is de droom voorbij nadat ze tegen de lamp zijn gelopen bij de grensovergang met Wit Rusland in het oosten

of met Polen in het westen. De meeste vluchtelingen zijn naar Moskou gevlogen, waar ze met auto¹s, bussen of

de trein over land naar het westen zijn gereisd.

Litouwen zou de vluchtelingen zonder problemen door

kunnen laten lopen, maar het land wil graag lid worden van de Europese Unie. Om te laten zien dat Litouwen

de grens goed kan bewaken heeft de regering de controles opgevoerd. Inmiddels hebben de smokkelroutes zich

dan ook verlegd van Litouwen naar de Oekraïne en Slowakije.

De voormalige Sovjetkazerne raakte twee jaar

geleden door de strengere aanpak overvol, maar nu is er steeds minder aanvoer. De mensen die er nog wel

zitten wachten vaak lange tijd op uitzetting naar hun eigen land. De Litouwse wet kent geen beperking van

het aantal dagen dat een migrant mag worden opgesloten, waardoor de vluchtelingen soms wel twee jaar in de

gevangenis zitten.

tekst Piet de Blaauw

foto's Piet den Blanken

![]() Old Red Army barracks in Pabradé, Lithuania, now are a prison for illegal migrants. Nobody of the two

hundred refugees from countries like India, Pakistan, Angola, Sri Lanka, Russia, Azerbeidjan and Bela-Russia,

wants to stay in Lithuania. This most southerly of the Baltic republics only is used by smugglers of people

as a gateway to the promised land: Western Europe.

Old Red Army barracks in Pabradé, Lithuania, now are a prison for illegal migrants. Nobody of the two

hundred refugees from countries like India, Pakistan, Angola, Sri Lanka, Russia, Azerbeidjan and Bela-Russia,

wants to stay in Lithuania. This most southerly of the Baltic republics only is used by smugglers of people

as a gateway to the promised land: Western Europe.

Despite the relatively low numbers, everything

indicates that the refugees are not welcome in Lithuania. High rolls of barbed wire span the barracks and

policemen with Alsatian dogs walk around the complex. Watch-towers keep an eye on the surroundings.

Photographer Piet den Blanken visited the prison and asked the refugees where they preferred to go.

Germany and the Netherlands were mostly mentioned. There, after arrival, a house and a job were

immediately available, the migrants knew for sure. The smugglers of people have their interest to

keep alive these myths as they raise with these ideas the desire to travel to Europe.

But for

the prisoners in the Lithuanian barracks the dream ends when they are arrested at the border with

Bela-Russia in the eastern part of the country or at the border with Poland in the west. Most of

the refugees came to Moskou by plane from where they traveled with cars, buses or by train over

land in western direction.

It would be easy for Lithuania to let the refugees continue their way,

but the country wants to be a member of the European Union. To show her capability to guard the borders,

the government raised the control. That is why the smuggle-routes changed from Lithuanian to Ukraine and

Slovakia. The former Sovjet barracks filled up strongly two years ago by tightening up the controls at the

borders, but now less people are arriving.

The people in the prison have to wait a long time before

they are being expelled to their own country. The Lithuanian law defines no restriction of the time a

migrant can be locked up, that is why refugees sometimes are imprisoned for two years or more.